With over 44,000 spider species in the world2, how do you pinpoint one species to study? Dr Lynda Rayor, from Cornell University, has done just that, presenting a seminar at Macquarie University on one very unusual spider species – Delena cancerides.

D. cancerides is an Australian huntsman spider within the family Sparassidae3 that exhibits a prolonged sub-social behaviour2. This is quite peculiar considering that, according to Dr Rayor, sociality is rare in spiders other than initial maternal care of egg sacs. Furthermore, the majority of spiders that are social spin webs, which allows the spiders to cooperate on prey capture and reduce their silk costs. However, D. cancerides also exhibits this trait of a tightly associated, long lasting colony, with one very big difference – it does not build webs3.

Photo of D. cancerides – an adult female and offspring. Source: Agnarsson, I., & Rayor, L. S. (2013, p. 896).

Photo of D. cancerides – an adult female and offspring. Source: Agnarsson, I., & Rayor, L. S. (2013, p. 896).

The miniature commune

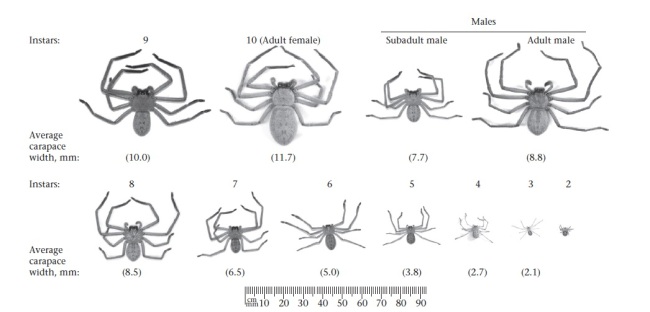

Dr Rayor has observed colonies of 20 to 200 individuals living in a retreat under the bark of Eucalypts, Casuarinas or dead Acacias. The retreat comprises of a matriarch and her offspring of various cohorts (or ages)3 (see image below). Dr Rayor’s research has shown that individuals will disperse from the colony only once they are sexually mature (approximately 1 year old).

Instars – the different age groups of D. cancerides in the colony. Source: Yip, E. C., & Rayor, L. S. (2013, p. 1162).

The edges of the retreat are sealed with silk at the top and bottom, which according to Dr Rayor, is large enough for the adult female to guard the entrance. This could possibly be a mechanism of protecting the colony and keeping watch, making it hard for predators to access the retreat3.

Next of kin?

Yip et al. (as cited in Yip & Rayor, 2011) determined through allozyme analyses (a type of genetic analysis) of D. cancerides colonies, that most of the offspring were either full or half siblings. Interestingly though, there were actually unrelated spiders in up to half of the colonies studied. Dr Rayor explains that this is possible because spiders can get lost when foraging at night – they go home to the wrong colony! Individuals of less than 6 instars have a greater possibility of being integrated into the new colony. Older spiders are usually seen as a threat and shooed away, or killed.

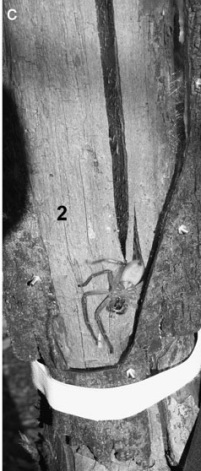

D. cancerides appearing from under the bark of a tree. Source: Yip, E. C., & Rayor, L. S. (2011, p. 1938)

D. cancerides appearing from under the bark of a tree. Source: Yip, E. C., & Rayor, L. S. (2011, p. 1938)

The sibling conundrum

The study by Yip & Rayor (2013) found that younger D. cancerides of 4th to 5th instar were heavier when their older siblings were present – an indication that younger siblings can benefit from the presence of their older siblings.

Dr Rayor has observed older siblings sharing prey with up to 22 of their younger siblings. She states that although this only occurs 5% of the time (which may not seem like much), it is actually quite significant considering this is not a very common occurrence in spider species. Dr Rayor explains that it is less energy intensive if older spiders share their prey than to continually protect it from younger siblings.

However, it may not all be about prey sharing. Yip & Rayor (2013) explain that the heavier weights could be a result of younger siblings scavenging the prey scraps from the older siblings – not prey sharing. This process can also be referred to as a producer-scrounger system, and may be similar to what has been described within the literature as ‘tolerated theft’ by primates.

Such leisurely dispersal

Why does D. cancerides remain in colonies until they are sexually mature before they disperse? There are two major reasons: cost and habitat saturation3.

#1: The very little cost

- There is no major food competition within the colony, even if the older spiders have to share some prey with their younger siblings3.

- Offspring can benefit from their mum – she’s very efficient at eliminating predators with her aggressive attitude. This is particularly handy for the youngsters that cannot defend themselves very well3.

- Individual tolerance to each other (or lack of cannibalism). Dr Rayor’s new research suggests that the lower metabolic rate of D. cancerides means they can survive on low prey availability, leading to a low cannibalism rate amongst this species.

#2: Habitat saturation

There is no spare space for spiders to disperse – retreats are usually 100% occupied. A small spider would find it extremely difficult to secure a retreat that wasn’t occupied. Therefore, waiting until they are larger and more able to defend themselves is a useful tactic3.

Food (or spiders) for thought

With increasing habitat fragmentation and destruction leading to further habitat saturation, could D. cancerides develop a more relaxed strategy to the kids staying at home? Furthermore, Dr Rayor found that as habitat saturation increases, the occupants become larger, as they are best at competing for new resources (survival of the fittest). Does this mean that, in an evolutionary sense, D. cancerides may become a larger species in the future?

References

1 Agnarsson, I., & Rayor, L. S. (2013). A molecular phylogeny of the Australian huntsman spiders (Sparassidae, Deleninae): Implications for taxonomy and social behaviour. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 69(3), 895-905. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.015

2 Rayor, L. (2014, March 5). Adaptations for living with cannibals: Evolution of sociality in Australian huntsman spiders. BioSeminar. Conducted from Macquarie University, North Ryde, NSW.

3 Yip, E. C., & Rayor, L. S. (2011). Do social spiders cooperate in predator defense and foraging without a web?. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 65(10), 1935-1947. doi: 10.1007/s00265-011-1203-5

4 Yip, E. C., & Rayor, L. S. (2013). The influence of siblings on body condition in a social spider: is prey sharing cooperation or competition?. Animal Behaviour, 85(6), 1161-1168. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.016